Finding phytoplankton and finding myself

Contributor: Tessa Rock, Maine Sea Grant Undergraduate Scholar

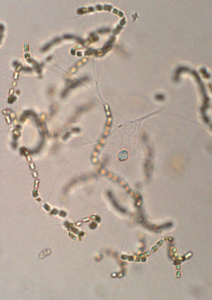

When you wade in the ocean and let the salty water flow around you, what is running through your mind? Is your mind relaxing, are you looking for fish, or maybe you’re anxious a crab is going to pinch your toe? I bet you aren’t thinking about the microorganisms surrounding your feet, phytoplankton just drifting with the currents. There are these beautiful organisms in the ocean that generally you cannot see unless you use a microscope. Each species is unique with its shape and special features. I study phytoplankton, microorganisms in marine and freshwater systems that get their energy from the sun, and to be more precise I take photographs of them and determine if tidal stages, moon phases, and predation significantly control their abundance.

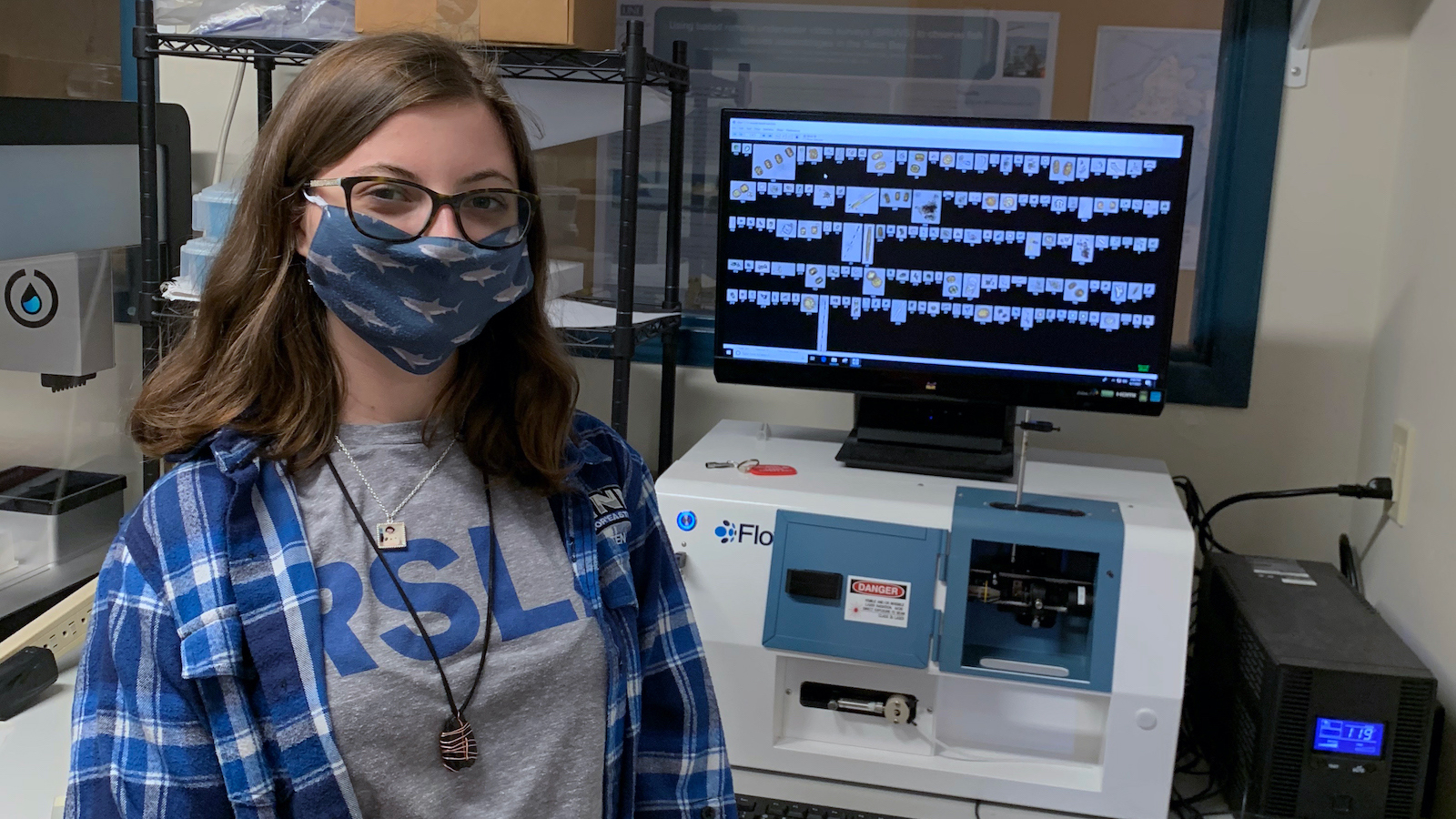

I have been involved in undergraduate research at the University of New England since the beginning of my first year, in 2018. Every week, I would be in the Zeeman lab with water samples from Biddeford Pool estuary and a microscope, hoping to adjust the light and turn the dials just right to focus on an organism so that I could then draw it in my journal. Once I drew the phytoplankton, I would then patiently look through an identification book, frequently looking back at the organism in the microscope and the book to make sure I had the correct species. I have now become so familiar with the pages of an identification book that flipping through it is like flipping through my memories. Now that I have familiarized myself with the species in this ecosystem, I conduct research using a Flowcam® from Yokogawa Fluid Imaging Technologies, Inc. This instrument combines light microscopy, the basics of how a microscope focuses light on small creatures, and flow cytometry, water being pulled through a system of tubes, to capture images of anything in a water sample. A Flowcam® is a relatively new technology for aquatic research. I use it for two reasons: to learn how the machine functions, and to speed up the process of identifying phytoplankton. I can look at many water samples and identify the organisms in a quarter of the time it would take me if I were to use a traditional microscope. Along with the images, the Flowcam® simultaneously captures numerical data that I can then use for statistical analysis. This machine is like an old friend now, I give it pep talks when it doesn’t feel like working, and it brings me peace as I sit and watch the plankton flow by on the screen.

My research particularly focuses on the tidal stages in Biddeford pool and if the tidal stages at two distinct locations affect the abundance of phytoplankton. This project essentially has two questions that I am trying to answer: do any of the factors significantly affect phytoplankton abundance and are there any statistically significant differences between the species on the tides. Every neap and spring tide, I am up to my knees in flowing water, hoping I am not stepping on any periwinkles, holding a mason jar in the river to collect the phytoplankton. Once I go back to the lab, I filter the samples and take volume measurements. I run three vials of each sample through the Flowcam® for 20 minutes each. As I sit there watching the screen that shows me the images captured, I see phytoplankton that have hairs for protection, a chained body, bright green chloroplasts for photosynthesis, or even golden centric phytoplankton that have many individual chloroplasts. These images capture the hidden beauty of phytoplankton.

My research has implications for understanding the broader ecosystem function within Biddeford pool. Scientists are still unsure of what affects the phytoplankton abundance in this ecosystem, so it is pertinent to learn this as we work to make sure our ecosystem stays healthy. Phytoplankton are food for many species, including shellfish such as mussels and clams. If shellfish ingest toxic phytoplankton, the toxin could be passed along and harm anyone who consumes those shellfish. Since phytoplankton are microscopic, it’s hard to understand how these creatures are important to us. So, by bringing together photographs, statistical analysis, and broader implications, I am able to show others how it is essential to care about the microscopic beings that live in our backyard.

Now that I am ending my third year as an undergraduate, I have been able to watch myself grow as a scientist. I was an odd case; I came into college knowing what I wanted to do. My life took a new direction in the summer of 2019 when I received a research grant to conduct this project, and I slowly realized that, while research will always be a constant in my life, what I apply that research to has changed. As I have been on this journey, I have been lucky enough to have the opportunity to be awarded a Maine Sea Grant undergraduate scholarship. Receiving this scholarship and creating new contacts with people from Maine Sea Grant has given me more inner strength and trust within myself. I know I can be a successful scientist, but sometimes it’s hard to believe in yourself. Receiving a scholarship from an organization as distinguished as Maine Sea Grant, gave me more strength than I thought imaginable because it showed me that the research I am doing now is significant, and that I can make a difference in this world.