On the appetites of baby lobsters

Author: Alex Ascher, a University of Maine graduate student working with Drs. Rick Wahle and David Fields on a research project funded through the National Sea Grant American Lobster Initiative, the NSF-funded Maine eDNA program, and Maine DMR’s Lobster Research Collaborative.

When people think about lobsters, we tend to think about eating them. Who has the best lobster roll? Should it be warm with butter, or cold with mayo? Maybe get a little fancy with a whole grilled lobster? In my research, I turn this thinking around – I want to know what and how much lobsters are eating. In particular, I’m curious about baby lobster diets.

Lobsters start their life cycle as eggs held underneath their mother’s tail for 9-11 months. Upon hatching, they swim up from the seafloor and live in the water column as planktonic larvae for roughly six weeks. During this time, they need to avoid getting eaten by predators, search for suitable living quarters on the seafloor, and accumulate enough energy to continue growing. A few good, square meals as a larva may make all the difference in determining whether a lobster successfully settles to the seafloor and reaches adulthood. Scientists who study the earliest life stages of marine fish and invertebrates have long wondered how getting enough food during this vulnerable larval period relates to larval survival and long-term trends in adult populations. Specifically, my lobster research seeks to examine the relationship between diet and settlement success – whether the amount of food available significantly affects the ability of lobster larvae to transition from their planktonic phase to juvenile life on the seafloor.

Despite a booming adult lobster population in the Gulf of Maine, scientists have recorded decreasing amounts of settling lobsters in many areas of the Gulf over much of the past decade. In other words, although we have many adult lobsters capable of producing eggs and larvae, we do not see similar numbers of the planktonic larvae settling to the seafloor to become juveniles. In my research as a PhD student in the Wahle Lab at the University of Maine, I focus on understanding what we call “The Great Disconnect” between a booming lobster population and falling settlement numbers.

Scientists have recently found that this decrease in lobster settlement may be linked to a decline in a food source: a copepod species called Calanus finmarchicus. As an energy-rich planktonic crustacean, C. finmarchicus holds a critical position in the food web of the Gulf of Maine. It’s a main-stay of both herring and right whale diets, and may be similarly critical to the survival of lobster larvae. If lobster larvae really depend on C. finmarchicus as a food source, then its decline may lead to starvation for them.

This starvation theory challenges some long-held ideas…you see, many researchers originally thought that it was unlikely that early planktonic life-stages, such as lobster larvae, were prone to natural starvation simply because wild larvae are rarely observed in a starved condition. Research now shows that crustacean larvae are actually quite sensitive to starvation, and this starvation sensitivity is something we have observed in our own lab. When lobster larvae are starved for just a couple of days, they tend to become inactive, almost comatose, well before they die. This sensitivity may even explain why wild larvae are rarely observed starving, as they may die, sink, or be eaten by predators before we can document them. In other words, there are a lot of signs pointing to the possibility that declining lobster settlement may be due to a food shortage in the larval life stage.

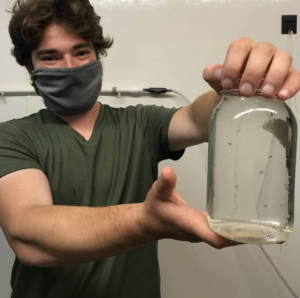

To explore this idea, the Wahle Lab is collaborating with the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and the University of Southern Maine in a multi-investigator project to conduct field and laboratory studies of the food web interactions of lobster larvae and their prey. One of our lab experiments this past summer was designed to determine how the nutritional status of wild lobster larvae measure up to those reared under laboratory conditions. In the lab, we raised larvae on one of two separate diets: starved, or well-fed with the best naturally available live zooplankton we could get. Importantly, larvae in these two diet categories came from the same mothers and were raised at the same time. We kept all larvae at the same temperature, ensuring that the only difference in their environment was the food available to them. We are currently analyzing these lobster larvae for fat storage content to determine their nutritional status. Any differences we see between the two groups should be due solely to whether they were well-fed or starved. We will then compare these lab groups to wild-caught larvae to determine if their fat content is more similar to our starved or well-fed lab larvae. These data will help us better understand what lobster larvae are experiencing in the wild, and whether low settlement numbers may be caused by starvation or some other factor yet to be identified.

This type of work is made successful through collaborations like the Sea Grant American Lobster Initiative (ALI.) Identifying the necessary materials and methods for raising lobster larvae can be difficult, but the expertise of my co-advisors Dr. Rick Wahle (UMaine, Darling Marine Center) and Dr. David Fields (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences), as well as others in my lab, ensured a successful summer research season. Arriving in Maine as a new PhD student and a novice in lobster research, I found that being part of the ALI made it possible for me to meet researchers with similar interests throughout the Northeast region, and to learn about their research while sharing my own. The ALI also serves as a template for young scientists like myself on how to nurture meaningful collaborations to help us reach our research goals. Looking forward, I am excited to see what we will learn about lobster larvae, and to share our research with our colleagues in the ALI.