Tales from a Technician: Maine’s Largest Offshore Larval Lobster Survey

Author: Ruby Dener is a marine research technician working with Maine’s Department of Marine Resources on a research project supported through the National Sea Grant American Lobster Initiative.

As you dig into a lobster roll, drench a tail in butter, or pick some sweet claw meat, do you ever wonder how that lobster grew to become that iconic New England menu item in front of you? If you are enjoying a standard one-pound lobster, then you may be interested to know that about 7 years and 25 molts ago it was just a tiny, larval lobster beginning its life offshore.

To understand how lobsters grow and develop, my job as a research technician is to locate and collect larval lobsters across the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank. Working collaboratively with the Atlantic Offshore Lobstermen’s Association, the Maine Department of Marine Resources (DMR), Maine Maritime Academy, New Hampshire Fish and Game, Hood College, and industry members across New England and with support from the Sea Grant American Lobster Research Program, we set out this past summer to learn more about lobster larvae during the different stages of their life: where they are, when and how long they stay in that location, and what they eat while they are there.

It may come as no surprise to Mainers that the American lobster fishery is the most valuable single-species fishery in the nation. The overwhelming majority of U.S. lobster are caught in the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank. Although the landings (report of the total number or weight of all lobsters caught, brought to market, and sold) in this region appears healthy and thriving, researchers have seen a decline in the number of juvenile lobsters settling on the seafloor since 2012.

The cause of this decline is unknown, but it casts a cloud of doubt for the future of the fishery and highlights the need for studies about the distribution and development of lobsters during the earliest stages of their lives. In 2018, DMR scientists began an inshore small-scale survey of lobster larvae with sampling stations at 0-3 nautical miles from shore. This provided a snapshot of local inshore larval abundance, but questions remained as to how results may differ farther offshore, during different times within the hatching season, or across various substrate types. Other researchers in New England have conducted similar localized inshore larval surveys, but this study is the first of its kind to analyze the Maine coast as a whole, fully spanning the hatching season, and including both in and offshore (up to 25 nautical miles) sampling. Research like this with the potential to answer big, new questions was especially interesting to me because every trip came with its own surprises and challenges.

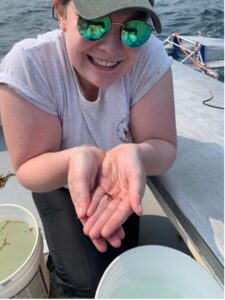

Larval lobsters begin life as one of thousands of eggs held under a female lobster’s tail. Once they hatch in the late spring/early summer, lobster larvae move closer to surface waters and become part of the planktonic community. They go through three larval stages before reaching their postlarval form that swims down and settles on the bottom. My job for this research project was to capture lobsters in these first four stages of life using a neuston net, which is a specialized net pulled through the surface layers of the ocean. It filters water to collect all of the plankton (including larval lobsters) it encounters. The net often collected additional debris (like seaweed), which I carefully rinsed to dislodge any critters before sorting the sample. I then rinsed and poured each sample through a fine-mesh sieve to make sure I didn’t miss any animals. During this process, we are careful to remove leftover debris and release living bycatch (such as larval fishes) before counting and preserving all of the larval lobsters.

To help us understand what lobster may be eating in their larval stages, we also sampled the water for other kinds of even smaller crustaceans that live throughout the water column. For these tows, I used a plankton net with an even finer mesh than the neuston net. The plankton net was not towed behind the vessel, but instead lowered over the side of the vessel to sample water vertically from the seafloor and back up to the surface. The depth of the deployment depended on the site, but max depths reached ~800 feet. The net did not reach the substrate, but rather was pulled back up when it was between 10-20 feet off the bottom, effectively sampling the entire water column. Like the larval lobsters, these plankton samples were also preserved for later examination.

Offshore sampling can be full of surprises and challenges. Since we really didn’t know what to expect each day on the water, I was trained to prevent any worst-case sampling scenarios: how to effectively rinse and remove seaweed or avoid sticks/debris that could rip the net, and how to adjust to changing conditions on the water. What I was not prepared for was the unexpected presence of hundreds of thousands of salps in our tows. These small and gelatinous tunicates clogged the nets and just about swallowed up everything of interest. The first time I noticed the net was towing abnormally, we pulled it out of the water to find ~20 pounds of salps! I didn’t know what to do, but after the shock wore off, the three of us (the lobsterman I was sampling with, his 11 year-old daughter, and I) started sorting. It was tedious, but we examined every single salp, carefully poking around for larval lobsters. This kind of sorting took a mind-numbing amount of care and attention to ensure we didn’t miss anything, but it paid off. In the midst of some of the worst salp bloom, we actually beat the DMR record for most postlarval lobsters caught in a single tow: in a three-minute tow, we counted 52! It was a blessing in a (gelatinous) disguise.

Results of these tows are still being analyzed but will hopefully provide greater insight into larval lobster biology in the Gulf of Maine and Georges Bank. It was an incredible feeling to be tasked with conducting the Gulf of Maine’s first broad-scale offshore larval lobster survey, and I feel honored to have contributed to the improvement of larval lobster monitoring that may help to predict future fishery recruitment and inform future management strategies. My favorite part of the experience was working collaboratively with fishing industry members. I spent hundreds of hours onboard their vessels getting to know them and chatting about anything and everything. To hear their thoughts and experiences on management issues (both new and old) provided a unique perspective and insight into natural resource management that is often lacking in traditional environmental education. The commercial fishermen I worked with had an incredible historical knowledge of the places they fish and work, and this experience helped to solidify my belief that marine science and fisheries management greatly benefit from the involvement of industry members. To watch a seasoned lobstering crew light up with excitement when we caught something funky, or hop around with glee watching a late-stage larval lobster swim around the bucket was a joy and a privilege. Their curiosity and genuine concern for any and all things oceanic was unmatched, and their willingness to commit their time and energy to a project like this just goes to show that the love of lobster runs deep.